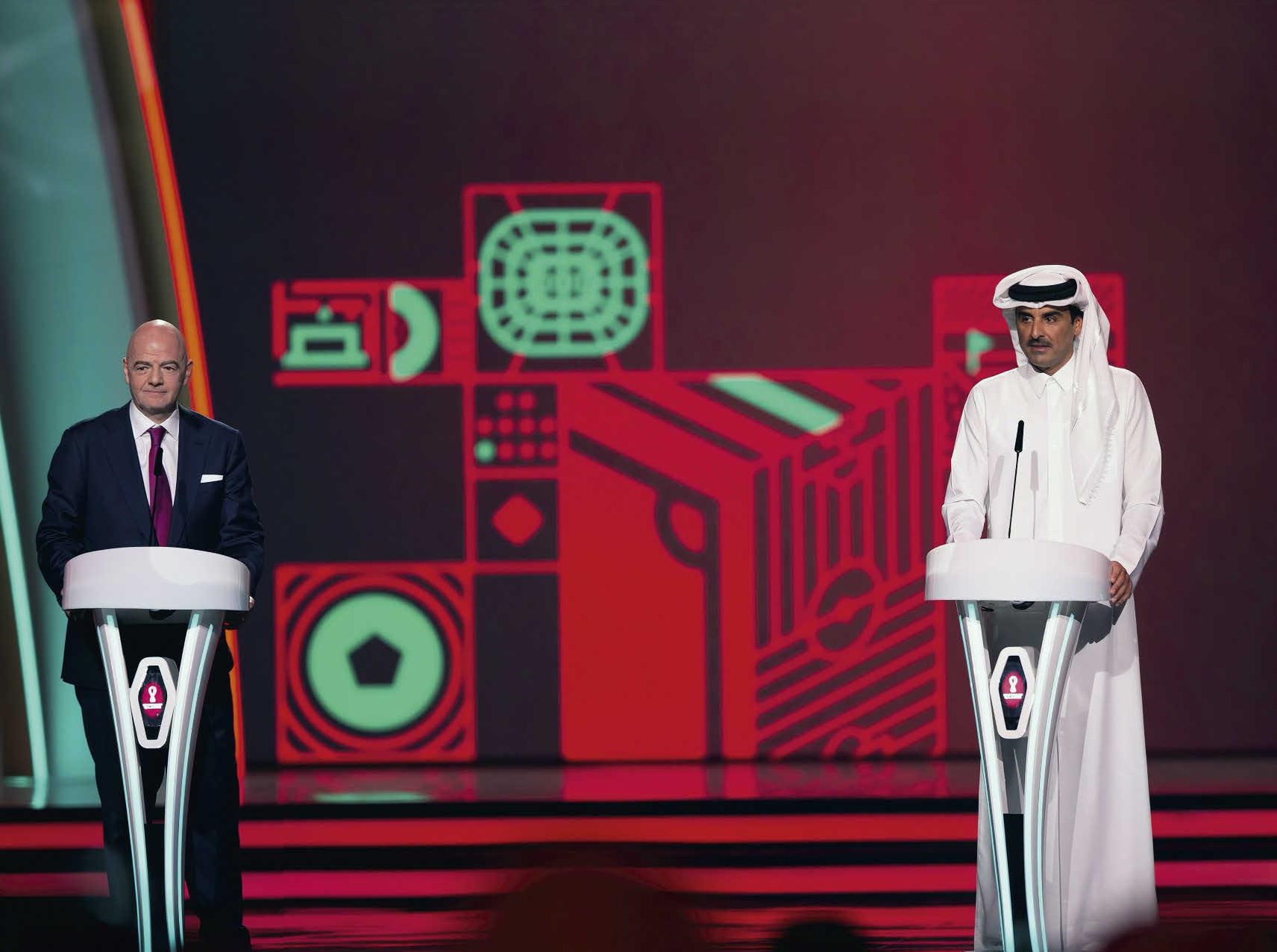

Qatar faces the goal

For the very wealthy Gulf emirate, this is the moment of truth. The World Cup kicks off on November 20. It will be necessary to be at the height of a planetary event, at a time when declarations of boycott are multiplying. And in a more than demanding geopolitical, security and health context.

In a few weeks, in this small presqu'île clinging to the Arabian Peninsula on the Saudi border, the 22nd World Cup of soccer will be played. A first time for the Arab world, a first time in the Muslim world. A World Cup in a country of 11,000 km2, a little larger than Lebanon or Gambia. A World Cup that will run from November 20 to December 18, ending a week before Christmas, on Qatar's national holiday. The result of a deliberate FIFA policy consisting of making the most prestigious of the competitions travel in the four corners of the world, outside its natural territories of predilection such as Europe or the Americas. We do remember with a true emotion the 2010 World Cup in South Africa, with this unforgettable, moving image of a frail Nelson Mandela, wrapped up in his coat, arriving in a small car on the pitch, the day of the opening match... Qatar is a particular and daring choice that was made twelve years ago (the USA was the other candidate) and which has given rise to a litany of criticisms, investigations for corruption, controversies, and the involvement of high-ranking political personalities (such as the former French president Nicolas Sarkozy). The competition will also be played for the first time in Western winter, summer being unbearable in the heat of the Persian Gulf. It will gather 32 teams and should attract more than 3 billion viewers, Qatar being relatively well placed – at “equal distance” – on the world time zone map. A World Cup in a micro-State, wealthy, with no great soccer tradition, which will be marked by the threat of Covid-19, the pandemic that never ends. A World Cup in a strategic country, first exporter with Australia of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in the world, which takes on a special significance with the war between Russia and Ukraine. A World Cup in the midst of climatic, geopolitical, military and economic turmoil, with record inflation, wheat and gas shortages, social tension on a global scale, a great celebration at a time when any spark could set the world on fire...

THE WORLD CUP OF SHAME ?

In addition to this particularly threatening atmosphere, there is a real trial of legitimacy. A wave of criticism with no concessions. In particular, an active boycott campaign. Essentially in Europe, in France, in the Nordic countries, also via NGOs and elements of the civil society. Politicians and sometimes players are being strongly encouraged not to make the trip to Doha, or to protest in one way or another. Also, viewers are being urged not to turn on their TVs. Some media outlets announced that they would not cover the event, while others spoke without shades of a "World Cup of shame"…

The "indictment file" is heavy. First of all, there is the ecological, environmental and energy cost. This comes right after a tough summer in the northern hemisphere: high temperatures, drought and forest fires. This will be a "carbon-intensive" World Cup in this sudden period of great sobriety, with these eight air-conditioned stadiums of 40,000 to 80,000 seats, including seven new ones. Another major point of accusation is the number of workers who have lost their lives during the construction of the infrastructures. The difference goes from 3, according to official Qatari sources, to nearly 3000, even 6500 according to NGOs. Of course, finally, there is the question of democracy and human rights. The supposed religious militancy, the doctrinal Wahhabism. There are also concerns about individual freedoms during the competition, rules penalizing homosexuality, “displays of affection” or the consumption of alcohol in public.

A LIABILITY THAT IS A PROBLEM

All this deserves some nuances. Yes, from an environmental point of view, the World Cup in Qatar raises questions. But we should have thought of that beforehand. (and it remains to be seen whether the air conditioners will really be used). The Qataris say they have done their utmost to run the competition with the least possible ecological costs. And all the mega-events of this type raise serious questions in the era of energy sobriety in which we are willingly or unwillingly entering. Whether it is the Summer or Winter Olympics, or even the Tour de France with its huge “caravan” following. The next World Cup (the 23rd) will be held in three countries: the United States, Mexico, and Canada. This implies insane travels of several thousand kilometers, a competition spread over three or four time zones, with hours of air travel involved. And a roster of teams that will increase from 32 to 48. But for the moment, no one is talking about reprofiling this gigantic project. Russia, the host of the 2018 edition, was also threatened with an active boycott, especially by the United Kingdom, amid the Skripal affair (the attempted assassination of a former Russian double agent and his daughter in Salisbury, England). Moscow had also annexed Crimea in 2014 and was waging a ruthless bombing war in Syria. The human rights record was not particularly enviable. This did not stop the party from going on, with many heads of state gathered during the competition (including Emmanuel Macron and Croatian President Kolinda Grabar-Kitarovic during the final). Going back a little further, the World Cup in Argentina in 1978 was played at a time when the country was led by generals and repression. The two Mexican editions (1970 and 1986) were played at altitudes that challenged the human physical condition. The question of corruption, of "influence" in the attribution procedures, is certainly not specific to Qatar, certainly not new to FIFA, nor to the International Olympic Committee (IOC). There were even investigations for the 2006 World Cup, awarded to Germany.

The question of workers is sensitive in Qatar, as it is in the entire Arabian Gulf. Still, the World Cup has made the organizer partially bring itself "up to standard" by reforming part of its "Labor Code": introduction of a minimum wage, guaranteed benefits, dismantling of the kafala system... The same is true on the political front, where the competition has forced the emirate to open its doors. The authorities have somewhat allowed journalists and NGOs to circulate and investigate with relative freedom. Questions that are of concern, such as national representation, the elective power of citizens, and freedom of expression, have been put on the table. In these spats of criticisms without concessions, there is a some truth and real questions. But certainly, also serious clichés and prejudices about a Gulf monarchy, an Arab country, a Muslim country, "backward", "which would finance the Islamists of the whole world". Even if Qatar is far from the societal and political liberalism of the West, from "mature" democracies, it has also been experiencing a real modernization for several years, accentuated by the prospect of the World Cup. And if criticism is often strong in Europe, this is not necessarily the case elsewhere, in the "South" and in the emerging worlds, where the attacks often seem unfair. What should we do to be climate and politically correct? What is a perfect democracy? If China was able to host the Winter Olympics, Qatar should be able to host a World Cup, right? And should the games be played only in temperate climates, and only during the western summer?

A SAFE COUNTRY

Basically, it’s Qatar, it’s very nature that raises questions. It has become one of the richest states in the world: with a GDP of more than 150 billion dollars for 3 million inhabitants, including a little more than 300,000 privileged citizens. A paradise that has invested all over the world in real estate, sports, football (Paris Saint-Germain among others), tourism, industries... The sovereign fund (Qatar Investment Authority) has nearly 450 billion dollars in assets under management. The emirate, the world's fifth largest producer of natural gas, is also a major key player at a time when energy is becoming scarce, when Russia is partially "exiting" the market, and when Europe is seeking to diversify its supply. Most recently, Qatar has just signed a mega deal with the French giant Total to increase its production with new offshore fields (North Field East and North Field South projects). The country is, unwillingly, the embodiment of loathed carbon-based economies. But it is also a key player in this period of scarcity, and even in the energy transition process.

A CAPITAL THAT EMERGED FROM THE SANDS

Doha, founded in 1850, was for a long time a small fishing and pearl mining village. Today, the capital doesn't have yet the stunning, over-the-top look of Dubai, but a city has literally risen from the sands in less than 30 years, with the iconic towers of West Bay. Across the bay, the usual archipelago of artificial islands, The Pearl, an impressive residential complex of luxury buildings and villas. And the development of the spectacular new town of Lusail, home to the stadium that will host the World Cup final. Education City proudly lines up its major international schools and universities, with the biggest American educational "brands" (Georgetown, Cornell, Texas A&M, Northwestern...). Qatar has invested in major architectural masterpieces, such as the Museum of Islamic Art (MIA, designed by Ieoh Ming Pei) and the National Library (Rem Koolhaas). Doha is also an international hub, a transit city, supported by Qatar Airways – one of the world's leading airlines – and its gigantic Hamad International Airport. On take-off or landing, the contrasts are striking. On one side, a view on the huge gas liquefaction plants. On the other one, a view on the Persian Gulf, on The Pearl, and on the private islets off the coast of the capital with palatial villas. Despite all its means, imperfection has paradoxically not totally deserted the place. The country is not very populated. The human resources are limited. Much is done and redone. The country is moving forward, the capital is growing, but there is this feeling of overheating, of often reaching the limits of what is feasible. On the outskirts, modest villas, "popular neighborhoods", and small businesses have not disappeared, sometimes giving the impression of large villages in the shadow of high-rise buildings. The atmosphere is certainly less festive than in Dubai. A certain rigorism is imposed. But here and there, in the hotels in particular, there are spaces where one can have a decent party (at least, foreigners).

REVIVING THE ECONOMY

Since the early 1940s, Qatar (then a British colony) has been an oil producer. It was also known that gas resources were available. The country, independent in 1971, emerged from precariousness and quickly joined the club of emerging countries. From the 1980s onwards, however, the tide turned, and the economy was hit by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries' (OPEC) production quotas, the fall in the price of oil, and the generally unpromising prospects on the international markets. This drastically dried up revenues. The proven reserves themselves were not sufficient to build an ambitious development plan. And the wells would be exhausted by 2030. By the early 1990s, Qatar was running out of cash. The country was in recession. "we had to borrow to pay salaries", said a minister at the time. The country was politically static, framed by religious and social conservatism. Qataris are of Wahhabi culture, the rigorous branch of Islam they share with their powerful neighbor Saudi Arabia. The head of state, Emir Khalifa bin Hamad Al Thani, is old school. He had consolidated the power of his direct family at the expense of other tribes and branches. In 1995, Sheikh Hamad, the ambitious son, deposed his father who had left for yet another trip abroad. Khalifa apparently objected to his second marriage to Sheikha Moza. The emirate had no long-term economic strategy. But Sheikh Hamad knew what it wanted to do. Modernize the country at full speed, guarantee its independence, especially from its powerful neighbor Saudi Arabia. And revive the economy by shifting to gas, especially with the exploitation of North Dome, in the country's territorial waters. This natural gas deposit was discovered by Shell in the early 1970s and is the largest in the world. The central objective, the paradigm shift, was to find a solution to transport this gas without the pipelines. Liquefied natural gas was the outcome. It required heavy initial investments. Hamad looked for partners and financing. Some countries, eager to diversify their energy resources, bet on the project. Japan and France in particular, with the multinational Total involved. The success was quite spectacular. Qatar became the world's largest exporter of liquid gas, the fifth largest producer of natural gas (after the United States, Russia, Iran, which shares the exploitation of the North Dome with Qatar, and China). And one of the richest countries in the world.

CREATING SOFT POWER

The economic miracle is followed by a desire to loosen the stranglehold of conservatism, without really officially renouncing Wahhabi dogma, nor political control. The term "absolute constitutional hereditary monarchy" remains essential. The emir rules and governs. He is the head of state and the head of government. Thus, it is difficult to politically go against the system. But even in the realm of public expression, the Al Thani are willing to take some risks. The system indeed seeks to contain conflict and dissent through internal arbitration, to avoid repression. A relative possibility of "discussion" exists. Cautiously, by playing for time, Qatar is trying to give itself an image of a monarchy that is certainly absolute, but reasonably modern and open.

The emirate is investing the world, multiplying strategic alliances and assurances. Qatar wants to create soft power, conduct a diplomacy of balance, create margins of maneuver and influence. Ensuring the protection and independence of the country remains the main objective. This is the approach that certainly presides over the creation of Al Jazeera TV channel in November 1996, a real revolution in the dreary world of Arab media. The channel played a decisive role in the Arab Spring. The United States has a huge air base in Al-Udeid, the largest outside its borders. At the same time, Qatar maintains natural ties with neighboring Iran. Ties between the two cultures date back to ancient times, and the two countries share the exploitation of the famous North Dome oil field. Qatar mediates in many conflicts. It created a multitude of allies and friends around the world. The most recent examples are the agreement between the United States and the Taliban in Afghanistan (under Trump, and before the chaotic withdrawal of the U.S. military under Biden), and the very recent mediation between Chadian factions. The country is also engaged in an active development aid policy, through the Qatar Fund for Development.

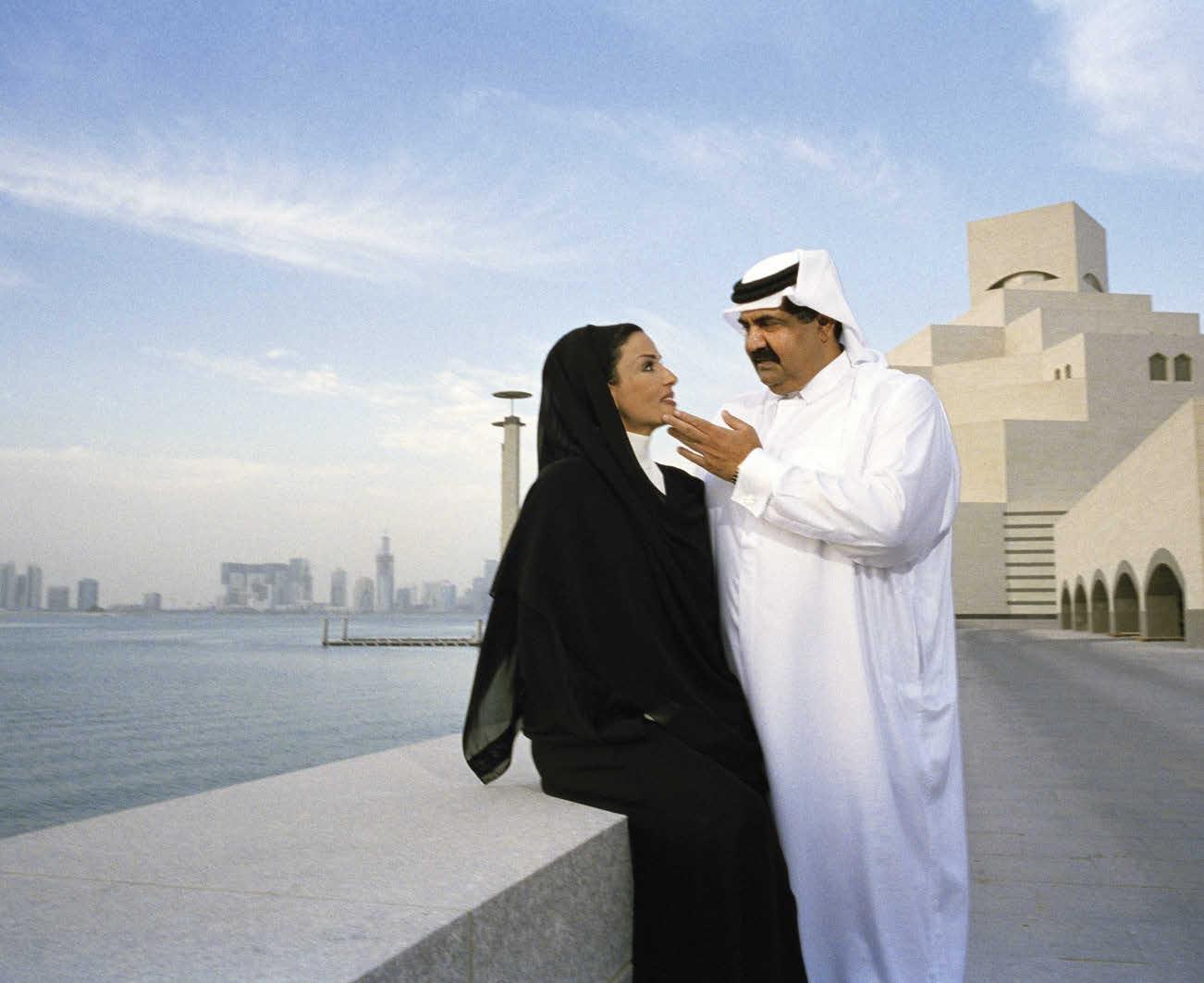

SHEIKHA MOZA, AN EXAMPLE

Emir Hamad's wife plays an essential role. The famous Sheikha Moza bint Nasser Al Missned, daughter of a liberal family, takes her part in the huge modernization project. In 1995, Sheikha Moza founded the Qatar Foundation. She made it the epicenter and the laboratory of reformist projects. Education became the necessary step for societal change. It is under her leadership that Education City was born and grew. She often wears caftans, with color and boldness. She appears in public. She expresses herself; she travels. She pushes taboos back, "loosens" society. And as a result, she carries with her a good part of the Qatari women, motivated by her example. Wahhabi Qatar is a surprisingly feminine space. Women are present in schools, universities, companies, offices, in the government, but also in public places. Couples can be seen in restaurants, or friends’ gatherings. The veil then takes a less austere tone. Most Qatari women are educated, financially independent, and not subject to the straitjacket of retrograde rules found elsewhere, such as in Saudi Arabia. One out of three marriages ends in a divorce, a real social phenomenon. This emancipation does not make only “ happy males ” in a society that remains dominated by powerful tribal and patriarchal codes. But nobody really wants to contradict the example set by Sheikha Moza and Father Emir Hamad. Father Emir, because, to everyone's surprise, he relinquished the throne in 2013 and handed power over to one of the sons from his second marriage, Tamim, then 33 years old.

The quiet transmission, without family turmoil, underscored the prominent role played by Sheikha Moza in the process of political consolidation and generational transition. The young Tamim slipped quite easily into the father's suit and the checks and balances were preserved. The program did not change: economic development, soft power, political independence, diplomatic balancing. The higher objective stayed the same : protect the independence, the sovereignty of the country, from the appetites of others. Qatari do not want to be prisoners of their geographical situation, with Saudi Arabia at their back and Iran at the front. They are looking for room to maneuver. By multiplying political bridges. By investing massively in friendships around the world. At the end of the day, it is as much about survival as it is about ambition.

BLOCKADE OPERATION

June 5, 2017. It is a shock. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Egypt (and others) announce the rupture of diplomatic relations and the establishment of a de facto blockade. Borders were closed, including the one between Saudi Arabia and Qatar (the only land border that Doha has). Air links were stopped overnight, with airspace closed to Qatar Airways. Students, visitors, and Qatari expatriates were ordered to return home by force. The trauma was intense on an economic level, but also on a human and intimate level. Marriages and ties have crossed borders for a long time. Relations between tribes are ancestral. Doha was accused of supporting Islamist religious movements and sowing disorder, in particular with the Al Jazeera channel. It was accused of being too close to Iran, to Hamas in Gaza, and to the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo. As far as the Qataris are concerned, the case against them was essentially brought by Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. In the lounges, one recalls the old disputes, the fact that for Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, Qatar remains a "fiction", a "hazard" without historical legitimacy. In the 1970s, Doha also refused to join the United Arab Emirates federation to play the solo card of independence. Since then, Qatar and the Emirates have never really stopped being rivals. The links with the Islamist nebula are considered an "easy" and "effective" argument used by the Saudis and the Emiratis to sway the opinions of Western countries, especially the United States. It also helps covering the ambiguous role of Saudi Arabia itself in the worldwide propagation of a rigorist Islam. As for the Iranian argument, the Qatari position is well known: the Iranians are their neighbors, their historical ties go back to the dawn of time, and they are partners in the exploitation of gas. Therefore, this operation was considered as vassalization project, the neutralization of a monarchy that is too rich and too powerful, of a regional counter-power that has, on the top of it, the audacity to host a World Cup... At the end, the blockade was not a success. Qatar proved to be much more resistant and resilient than expected, even if the bill was heavy. Above all, the crisis had acted as a painful revelation of weaknesses and dependencies. A brutal realization. The country has taken multiple measures to diversify its economy, increase its self-sufficiency, and maintain its attractiveness to the outside world. Despite the multiple pressures, Qatar has not been isolated, and most friends have remained loyal. Donald Trump had certainly raised the stakes, but without ever siding with the blockade. The blockade has even generated a passion, an unprecedented phenomenon of pride and citizenship. Qataris, expatriates, foreign workers, everyone took out the flag, discovered a nationalistic fiber in the face of danger. A fairly diverse society was born, a relative mix of citizens, residents and expatriates. Everyone closely ranked around a young emir and head of state, Tamim, who was strengthened by the ordeal. His popularity skyrocketed, and his famous drawn effigy appeared on the towers of the capital. From 2020, Kuwait led the mediation, while the United States was primarily concerned with the anti-Tehran front and with unifying the Sunni camp. Concessions were made on both sides. In December, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, Mohammed ben Salman, visited Qatar. On January 4, 2021, the crisis ended, alongside the blockade. Everyone moved on, almost as if nothing had happened. The world has become too dangerous for the Gulf countries not to find a minimum of common ground. With the blockade, after the blockade, with the World Cup, the Qataris are in any case determined to make "nationhood", even if it means for some to mask their uneasiness in front evolutions, the relative emancipation of women, the democratization of education, the opening of the country towards the outside world, the investments in tourism, the global business, the subtle spaces of freedom. A permanent dialectic between tradition, modernity, religion.

CREDIBILITY IS ON THE LINE

And now, finally, there is the World Cup. On November 20, the inaugural match will take place: Qatar vs. Ecuador. It will be very important to win or, at least, not to lose, and do well in the competition and possibly advance out of the group stage. But for the country and its 3 million inhabitants, citizens, or residents, it will be the moment of truth, the moment to take up a truly historic challenge. An organizational challenge, a security challenge, a logistical challenge, with hundreds of thousands of visitors, hundreds of daily flights with neighboring countries (flights which have themselves become the object of ecological controversy), and transportation and traffic jams... Brand new stadiums will be tested in real life. Visitors’ excesses will have to be, more or less, tolerated... The strict moral code that Qatar is trying to impose will be put to the test. The Qatar small bureaucracy will have to deal with sponsors, guests, FIFA requirements, VIPs, heads of state who will be there after all, friends who will absolutely want to come... A real culture shock in this almost island nation, heir to the desert, which will literally see the world come to its home. In the end, there will be a winner on the field. But for Qatar, the stakes are colossal. Reputation and credibility are on the line. It's about succeeding, about bringing a World Cup, the biggest sporting event on the planet, to a successful conclusion.